What A Night: Chapter Four

CHAPTER FOUR: NEW YORK CITY, NY

There was a point in my life, between 2002 and 2004, that I became very interested in stand-up comedy. At first I was a fan like everybody else—renting the most popular comedy specials and watching them anytime they were on television—but soon my interest grew more intense. Fortunately, I didn’t have to start my comedy collection from scratch; I was a hip-hop producer, which meant I already owned a decent amount of comedy albums on vinyl. I began revisiting these older albums from comedians like Richard Pryor and Steve Martin, listening to them with a completely different ear and appreciation. Eventually, my favorite comedians made their way out of my house and onto my MP3 player, just as any great album would.

The turning point came after I watched Jerry Seinfeld’s 2002 documentary, The Comedian. The movie was about Seinfeld’s life after the massive success of his sitcom and his decision to write a brand new stand-up routine from scratch. It was very rare for comedians to throw away all of their old ideas, but Seinfeld did just that. The Comedian movie was also the first time I had ever heard a comedian explain their creative process. Finding out the amount of trial and error that went into a great comedy routine was inspiring, and I saw a lot of parallels between comedy and music.

I eventually began exploring the local stand-up comedy scene. My first stop was an amateur night held every Tuesday at a placed called the Scarlet & Grey Cafe on Ohio State University’s campus. I loved how small and intimate it was. An added bonus was the fact that it was only a couple of blocks away from a weekly house music night called Restart that I already attended regularly. The close proximity allowed me to check out comedy night from 7 p.m. until 9 p.m., grab something to eat and then head directly to Restart.

Over the next year, I came to believe that comedians were the most brilliant minds in our society. While I already understood comedy on an emotional level, studying it from the other side gave me a greater understanding of the technicality involved in writing it. Their ability to catch things that other people didn’t notice and reintroduce them in a comedic context amazed me. Through comedy, they were able to talk about serious subjects like racism, sexism, religion, and poverty—things that might otherwise be off-limits or awkward for the average stranger to discuss. Comedy had the ability to disarm people’s defensive nature.

As my friends learned of my newfound interest, they would ask when I was going to get on stage and give it a try. They were shocked to hear that I had no plans for it. As far as I was concerned, I didn’t need a comedy club; I was a touring hip-hop artist with fans, so I already had a forum. My goal wasn’t to understand comedy so that I could be a comedian—it was to understand comedy so I could apply it to hip-hop.

So I began experimenting with comedy in my music.

This was the period of time where I wrote the majority of the humorous songs in my catalog, the most popular being “Big Girls Need Love Too.” Although “Big Girls Need Love Too” wasn’t released until 2005, I started performing it at my shows at the end of 2003 to test it out. The only difference was that I would perform it as a spoken-word piece instead of over a beat like a regular rap song. This taught me a lot about how to work a crowd. The first thing I learned was that it’s not easy to perform a silly poem during the middle of a hip-hop set, especially if the crowd was already drunk and loud. Not only did I have to set it up properly, but I also had to give it the proper pacing for a hip-hop audience. The second thing I learned was that there wasn’t much of a grey area for joking about women’s bodies—they were either going to love it or absolutely hate it. There was no middle ground. And even if I killed it, one young lady in the crowd might still hate me because she felt like I was talking directly to her. It made me see that I shouldn’t celebrate the ninety percent of the time it worked—I should be worried about the ten percent of the time it didn’t work. Those instances were enough to ruin the whole set or leave the majority of the crowd with a sour taste in their mouth.

My 2004 show at the Knitting Factory in New York City was one of those nights.

At the time, I was on the Plague on Wheels tour with my good friends and Rhymesayers label-mates, Eyedea & Abilities. The show was packed early and off to a great start. Based on the semi-cold reception I had received during my previous shows in New York, I had always felt like their crowds were difficult to rock. Well, not that night. That night they were going nuts as soon as I hit the stage. I rocked the first half of my set, then went into the “Big Girls Need Love Too” spoken-word piece.

Everything was fine during the first half of the first verse; people were laughing, all the rowdy energy was under control, and the crowd was loving it. Then I heard a voice from the back of the crowd yell something at me. Since it was pretty dark, I couldn’t see past the first few rows of people to see who it was coming from. I shook it off and continued with a couple more lines that got even bigger laughs from the crowd. That’s when I heard the same voice again, this time it was clear enough that the rest of the crowd started to notice. It was a woman calling me ignorant and heckling me.

“Then out of nowhere we hear a female voice come from the crowd saying ‘FUCK YOU! THAT SHIT IS WACK!’ among some other rants. My man Print does not take well to hecklers.” – DJ Rare Groove

I knew I had to handle it immediately. If there was one thing I learned from studying comedy, it was that the best comedians never let the hecklers win. From the oldest to the youngest, the best comedians would completely crush any heckler for disrespecting them. They knew they would look weak if they let the heckler get away with it, and looking weak would lead to other people joining in and ruining their entire show. I knew I had to act swiftly. It wasn’t the first time people had come at me crazy on stage, so I was well prepared.

I eventually realized the heckling was coming from a female in the left corner of the club. I paused and looked around, but since I still couldn’t see exactly who it was I said, “Oh you think I’m ignorant, huh?” A few more insults were thrown at me.

So I asked the crowd, “Do ya’ll think I’m ignorant?”

Three-hundred people yelled, “NOOOO!!!”

Then I asked, “Do y’all wanna hear more of this shit?”

Three-hundred people yelled, “YEAHH!”

Then I said, “Ok, well I want everybody in the crowd to raise their middle fingers up in the air.”

The entire crowd raised their middle fingers in the air.

Then I said, “Now, I want every single one of you to turn around to that corner over there, to that girl talking shit, and say FUCK YOU BITCH!”

The entire crowd turned around in unison to the girl who heckled me and screamed “FUCK YOU BITCH!!!!” right to her face.

Now say, “Blueprint’s the shit!”

“BLUEPRINT’S THE SHIT!!”

In most instances, performers dealt with hecklers one-on-one. Fuck that. I chose the opposite route and let the entire crowd put her in her place. All of the other artists on the tour looked at me like “Holy shit!!” It was the most extreme response I’ve ever had to a heckler in my entire career. The crowd was going nuts and completely on my side from that point forward, which helped me finish the last half of my set on a high note.

It would be a cool story if it ended there, but unfortunately it didn’t. As soon as I got backstage to gather myself, this girl I had never seen before walked into the dressing room and started cursing me out.

“As I make my way to the backstage door ready to celebrate, I hear loud screaming as I’m approaching the door. I open it to see Print getting screamed on by Ayanna, my man Sumkid’s plus one. Ayanna was a heavier set female who was on her Black Nationalist tip. Sumkid is shaking his head. Print is looking like who the fuck is this chick?” – DJ Rare Groove

I had no idea who she was and what was going on, but I didn’t appreciate it. My DJ heard all of the commotion and walked in. He didn’t understand why we were arguing either. Then she told us that she was the girl I had turned the crowd on and everything started to make sense.

She screamed, “You rude motherfucker! What the fuck is wrong with you? That was fucked up!”

I yelled, “Bitch, you shouldn’t have been tryin’ to hate. THAT’S WHAT THE FUCK YOU GET!”

Neither of us was backing down and the situation was escalating. None of the other artists knew who the girl was or how she got backstage. It was chaos. I could tell by the way she was getting more and more aggressive that she was about to take a swing at me. She was a pretty big chick too, so I didn’t doubt she would try it. Then, right when it was about to get physical, DJ Rare Groove stepped in to separate us. I told him he had to get her up out of there immediately because there was no way we were going to be backstage together after that altercation.

About 15-minutes later, Rare Groove returned backstage looking completely frustrated and in shock. He said, “My bad dog. I didn’t know she was gonna wild out like that when I put her on the guest list.” I wasn’t mad at him at all, but that situation did leave a bitter taste in my mouth about an otherwise great performance. Fortunately, I can laugh about it a bit more now.

What a night.

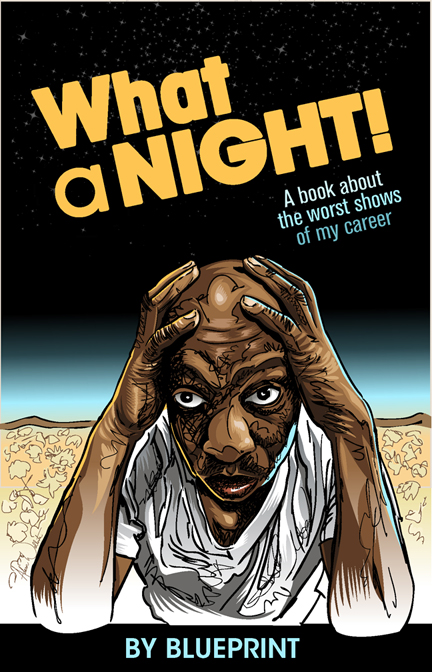

Order my new book, What A Night: A Book About the Worst Shows of My Career right now http://bit.ly/1vVF38T. Paperback version is signed and comes with a free 11×17 poster and a sticker.

BLUEPRINTMy latest album Two-Headed Monster is out now. Order/Listen here HERE